Jun 22, 2023

Bank of England steps up inflation fight with shock rate hike to 5%

, Bloomberg News

Imagining an A.I.-led central bank

The Bank of England unexpectedly raised its benchmark interest rate by a half percentage point, stepping up its fight against the worst bout of inflation since the 1980s and warning it may have to hike again.

The nine-member Monetary Policy Committee voted 7-2 for an increase to 5 per cent, the highest level in 15 years and the biggest move since February. Markets had priced in only a 40 per cent chance of a half-point hike, with most economists anticipating a quarter point.

Policy makers led by Governor Andrew Bailey reiterated earlier guidance pointing toward higher rates. They said nothing to rein in market expectations for rates peaking around 6 per cent by early next year, which would be the highest in over two decades.

“The economy is doing better than expected, but inflation is still too high and we’ve got to deal with it,” Bailey said. “We know this is hard - many people with mortgages or loans will be understandably worried about what this means for them. But if we don’t raise rates now, it could be worse later.”

The pound swung between gains and losses and gilts gained after the decision as traders raised their expectations for further rate increases. The market is now pricing a 30 per cent chance the key rate will peak at 6.25 per cent by February, which implies another one-and-a-quarter point of hikes.

“If there were to be evidence of more persistent pressures, then further tightening in monetary policy would be required,” Bailey wrote in a letter to Chancellor of the Exchequer Jeremy Hunt. He added: “The MPC will do what is necessary to return inflation to the 2 per cent target.”

In his response, Hunt said that “high inflation is the greatest immediate economic challenge that we must address,” and that the central bank has the government’s “full support” in its efforts to get inflation back to target.

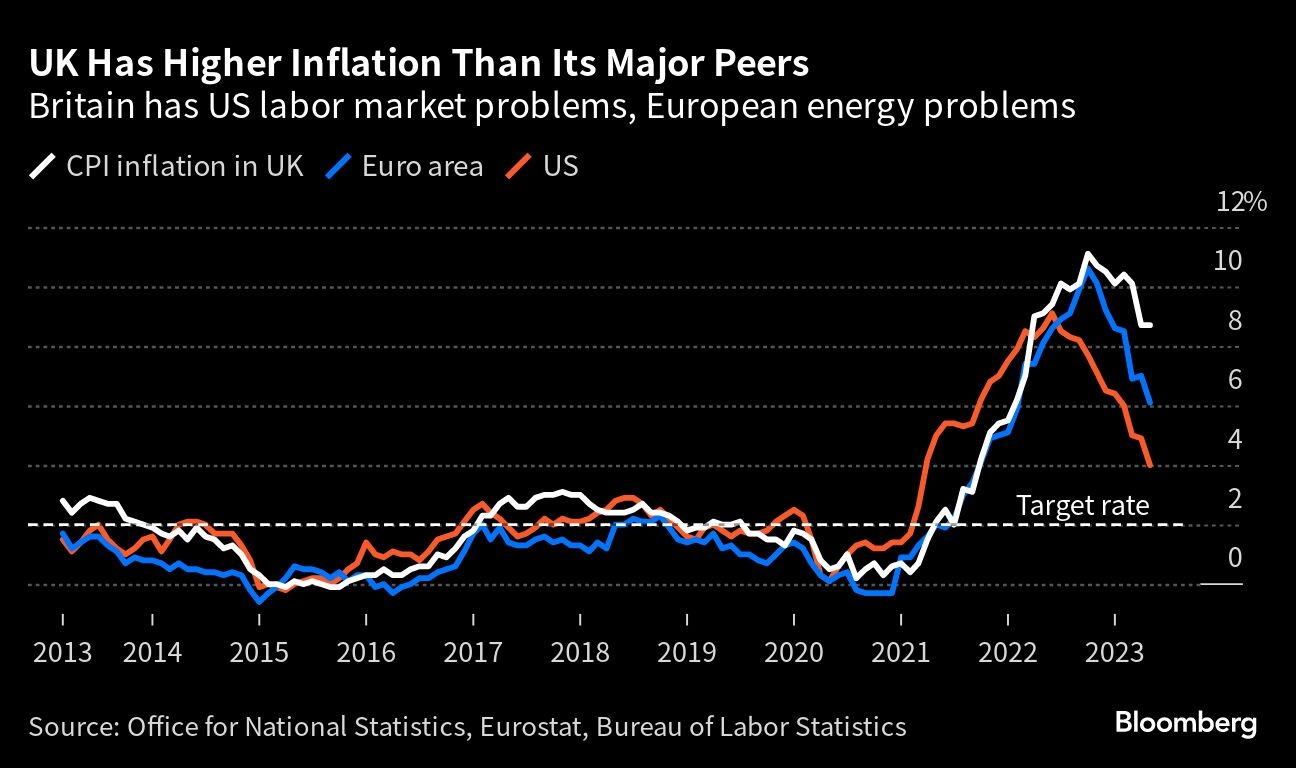

The decision announced Thursday suggests U.K. borrowing costs could keep rising through the summer even after the U.S. Federal Reserve paused its tightening spree. Britain remains an outlier in the Group of Seven nations, with consumer prices rising 8.7 per cent in May, four times the BOE’s 2 per cent target and more than double the rate in the U.S.

For borrowers, the move signals further hardship. Two year mortgage rates have tripled to more than 6 per cent since March 2022, and experts are warning of a mortgage “time bomb” as households refinance at unaffordable levels.

With at least 800,000 fixed mortgages due to move on to significantly higher rates in the second half of this year, lawmakers across the political spectrum are starting to blame Bailey and the BOE for failing to halt inflation earlier.

Read More: Sunak Spokesman’s Tepid Line on Bailey Shows Inflation Tension

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s government is facing calls to help struggling borrowers but has so far resisted them for fear of undermining the BOE. If rates hit market forecasts of 6 per cent, the UK will collapse into recession, Bloomberg Economics expects.

“High inflation is a destabilizing force eating into pay checks and slowing growth,” Hunt said in a separate statement. The government’s resolve to bring down inflation “is watertight because it is the only long-term way to relieve pressure on families with mortgages.”

Hunt is pressing high street lenders to help struggling borrowers, moving the issue up the political agenda at a time when the ruling Conservative Party is preparing to fight an election widely expected next year.

The minutes to the June meeting acknowledged that “second-round effects in domestic price and wage developments are likely to take longer to unwind than they did to emerge.”

It warned of “more persistence in the inflation process, against the background of a tight labor market and continued resilience in demand.”

Both services inflation and core inflation have been “stronger than projected.” Wages have also continued to rise faster than expected, the minutes said.

“A tighter labour market and impaired supply chains post-Brexit mean that the Bank faces a unique challenge in curbing inflation compared to its counterparts,” Yael Selfin, chief economist at KPMG U.K., said in an email. “If inflation continues to prove stubbornly high, we should expect interest rates to not only rise further but also to remain higher for longer before the cost-price developments come decisively under control.”

The two dissenting voices on the BOE’s rate-setting committee were external members Silvana Tenreyro, in her last meeting, and Swati Dhingra. They argued that the existing rate rises have yet to impact the economy fully and falling energy prices will push inflation below target by the end of the forecast horizon.

The minutes also argued that inflation pressures will soon ease. Consumer price inflation “is expected to fall significantly during the course of the year,” the BOE said. Goods inflation should come down as “producer output price inflation has fallen very sharply in recent months.” Food price inflation is projected to fall from current levels of near 19 per cent, it added.

Hunt told Bailey that he’ll meet with energy regulators next week to discuss how to ensure drops in wholesale prices are passed through to consumers. He also said he’s engaging with the food supply chain “on potential measures to ease the pressure on consumers.”

BOE officials will draw up new forecasts for growth and inflation in time for the next decision due on Aug. 3. Bailey, Tenreyro and BOE Chief Economist Huw Pill are all scheduled to speak next week.

With assistance from Elina Ganatra, Stuart Biggs and Alex Morales.